In the final keynote speech at the 2012 Edinburgh World Writers' conference, China Miéville asks what the future holds for the novel in cultural, political and digital terms - and concludes with a demand for salaried writing

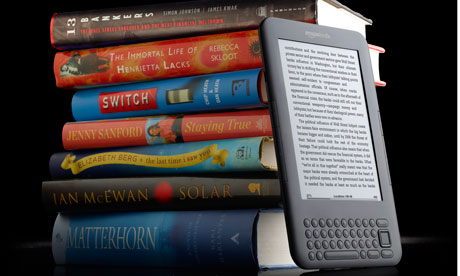

China Miéville: 'we approach an era in which the digital availability of the text alters the relationship between reader, writer, and book' Photograph: AP

"I have just ... paid a depressing visit to an electronic computer which can write sonnets if fed with the right material," said Lawrence Durrell, at the session 50 years ago of which this is an echo. " ... I have a feeling that by Christmas it will have written its first novel, and possibly by next Christmas novel sets will be on sale at Woolworths and you will all be able to buy them, and write your own."

Notionally, the horror here is something to do with the denigration of human creativity. But Durrell is aghast in particular that these novel sets will be on sale at Woolworths - the tragedy, perhaps, might have been a little lessened if they'd been exclusive to Waitrose.

It's not clear how scared he really was. Futures of anything tend to combine possibilities, desiderata, and dreaded outcomes, sometimes in one sentence. There's a feedback loop between soothsaying and the sooth said, analysis is bet and aspiration and warning. I want to plural, to discuss not the novel but novels, not the future, but futures. I'm an anguished optimist. None of the predictions here are impossible: some I even think are likely; most I broadly hope for; and one is a demand.

* * *

A first hope: the English-language publishing sphere starts tentatively to revel in that half-recognised distinctness of non-English-language novels, and with their vanguard of Scandinavian thrillers, small presses, centres and prizes for translation, continue to gnaw at the 3% problem, all striving against the still deeply inadequate but am-I-mad-to-think-improving-just-a-little profile of fiction translated into English.

And translation is now crowdsourced, out of love. Obscure works of Russian avant-garde and new translations of Bruno Schulz are available to anyone with access to a computer. One future is of glacially slowly decreasing, but decreasing, parochialism.

And those publishers of translated fiction are also conduits for suspicious-making foreign Modernism.

Full story at The Guardian

Notionally, the horror here is something to do with the denigration of human creativity. But Durrell is aghast in particular that these novel sets will be on sale at Woolworths - the tragedy, perhaps, might have been a little lessened if they'd been exclusive to Waitrose.

It's not clear how scared he really was. Futures of anything tend to combine possibilities, desiderata, and dreaded outcomes, sometimes in one sentence. There's a feedback loop between soothsaying and the sooth said, analysis is bet and aspiration and warning. I want to plural, to discuss not the novel but novels, not the future, but futures. I'm an anguished optimist. None of the predictions here are impossible: some I even think are likely; most I broadly hope for; and one is a demand.

* * *

A first hope: the English-language publishing sphere starts tentatively to revel in that half-recognised distinctness of non-English-language novels, and with their vanguard of Scandinavian thrillers, small presses, centres and prizes for translation, continue to gnaw at the 3% problem, all striving against the still deeply inadequate but am-I-mad-to-think-improving-just-a-little profile of fiction translated into English.

And translation is now crowdsourced, out of love. Obscure works of Russian avant-garde and new translations of Bruno Schulz are available to anyone with access to a computer. One future is of glacially slowly decreasing, but decreasing, parochialism.

And those publishers of translated fiction are also conduits for suspicious-making foreign Modernism.

Full story at The Guardian

No comments:

Post a Comment